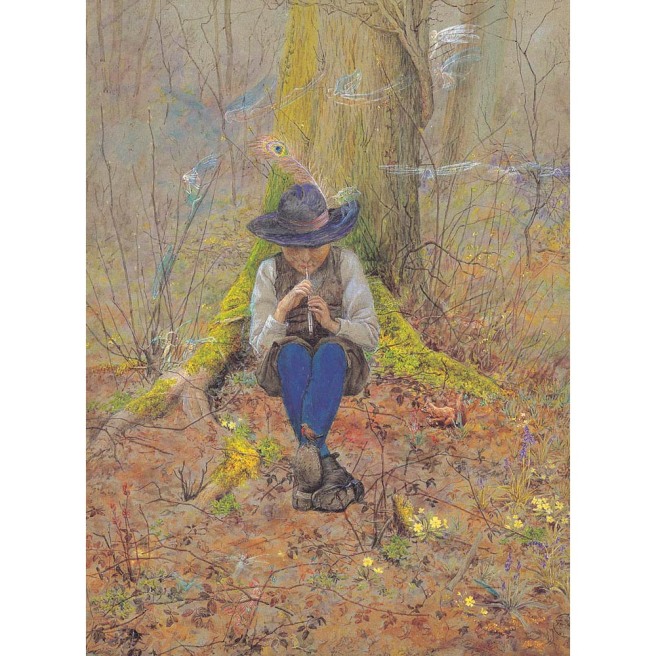

John Anster Fitzgerald, The fairy’s lake, 1866, Tate Gallery

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

(Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5).

In January this year the Fairy Investigation Society published a Fairy Census covering 2014-2017. The document makes fascinating reading and I will be examining its contents over a couple of posts. Here, I want to raise the intriguing question of what, exactly, we understand by the word ‘fairy’ in the early 21st century.

The data for the census comes from individuals across the world, although primarily from Britain, Ireland and the USA. They submitted descriptions of their fairy experiences to the Society and these give us an opportunity to consider what today is popularly understood to be ‘a fairy.’

We all think we know what a fairy looks like: we envisage either a fluttering girl or a small pixie in green. Whatever the detail, the fundamental assumption is that they are humanoids, closely resembling us. Nevertheless the Census, along with Marjorie Johnson’s Seeing fairies, confronts us with a body of sightings which within themselves are consistent and which challenge our conventional ideas. Some fairies apparently do not look like fairies at all.

Small animals

It is not unusual to hear of fairies and pixies being described as particularly hirsute and shaggy, with dark and unkempt hair, but a small number of encounters have been with mammalian beings that display human-like characteristics. Marjorie Johnson gathered together several of these.

During the summer of 1920 fairy seer Tom Charman spent nine weeks in the New Forest and repeatedly met with small cat-like creatures. Similar beings were described to Johnson by witnesses from Kent, Essex and Cheshire, but she also received a comparable report from Indiana- of a cat standing on its hind legs and wearing brown trousers. When disturbed, it ran away ‘like a rabbit.’

In his valuable little book, Somerset fairies and pixies (2010), Jon Dathen interviewed a Somerset farmer who recounted a sighting from his childhood, some seventy years earlier. Late at night he had sneaked downstairs to find a small person “like a hare done up in clothes” sitting in front of the farmhouse fire. He had long ears, whiskers and buck teeth, but he could speak- explaining he had come in to escape the cold. Later in his life, the farmer had heard of other hare-type pixies being sighted in the county.

John Anster Fitzgerald, The storm.

Furry shapes

A handful of reports take furriness even further. A woman on holiday in mid-Cornwall during the 1930s described how she regularly met some cliff dwelling pixies; both were about two feet in height. The male was a small human with some distinctive features but the female was covered in short dark brown hair with yellow rings on her body and arms, somewhat like a bee.

Two other accounts are even more surprising. During the early 1940s in Kent one woman was on a country walk when she saw a furry tennis ball rolling up a slope towards her. It briefly opened when it drew close to where she was sitting to reveal a pixie within- and then disappeared. Returning to Cornwall in the 1930s, a final witness on a coastal walk sighted a pisky who then changed into “a long furry black roll, which gambolled about on the grass and then disappeared.”

John Anster Fitzgerald, The painter’s dream.

‘Ent fays’

Over the last hundred and fifty years the identification of fairies with the environment and natural processes has become more and more commonplace. Some fairies are seen dressed in garments made from leaves and flowers, but it may not be especially surprising to find that supernatural beings are met with who appear to be more vegetative than animal. These are creatures whose body seems to be composed of vegetable matter; they may perhaps be subdivided into ‘ents,’ walking trees, and smaller hybrid entities.

The tree-beings can be tall, seven feet high or more, perhaps with faces showing in the bark of their ‘bodies.’ The smaller vegetation fairies appear to be far more mixed in their appearance. Some have bodies made of animated leaves and sticks, some are composed of a mixture of plant and insect elements, some are tiny leaf-like creatures. With more evidence it may very likely be possible to analyse these types further.

Charles Altamont Doyle, A creeper.

Monsters

Last of all, there is a collection of witness accounts that tests our conceptions of fairies to the limits. There are strange hybrid creatures: a dragonfly-fish, a frog-sparrow or a butterfly-bird. There are also semi-human forms: beings that are part human and part insect, reptile, dog, spider or frog, as well as fairies that seem to be a combination of traditional fairy and mermaid features. Some fays have appeared as huge tadpoles, another as an ape dressed in leaves.

Some other less conventional forms

There are various other classes of sighting which, whilst fitting within the conventional imagery of fays, still display some unique features.

Aliens

The boundaries between ‘aliens’ and ‘fairies’ are increasingly uncertain and permeable, it seems. In Seeing fairies a tiny number of witnesses mentioned beings with pronounced pointed faces or slit/ black eyes. The proportion of such sightings was distinctly higher in the Census, suggesting that the now-standard concept of a ‘grey alien’ may be shaping fairy experiences.

Humanoids

Although the commonest fay form is human, they are sometimes said to be noticeably disproportionate, being too tall or having overlong limbs. This is occasionally hinted at in Johnson’s reports, but spindly or gangly bodies are considerably more frequent in the Census, with bodies described as being very slender, long-limbed or above normal height.

Lights

The luminosity of fairies is often mentioned, but the last transformation is the eradication of the body altogether: the fairy is reduced to a point of light, which is often seen darting about. Johnson’s witnesses experienced this only a handful of times. In the Census fourteen per cent of cases were sightings of bright lights, of which nearly three quarters were moving. We may suspect here the influence of J. M. Barrie‘s stage representation of Tinkerbell in the minds of those having the experience.

John Anster Fitzgerald, The stuff that dreams are made on (detail).

Conclusions

On their own, these reports are so anomalous as to make no sense, but grouped together some sort of pattern does appear to emerge and it is possible to identify certain ‘species’ that are regularly sighted. Perhaps they are so different from the standard idea of fairy to demand a new name, but at present ‘faery’ is the only category to which we may assign them.