Vivien Leigh as Titania in Midsummer night’s dream

For many of us today, Titania has become the archetype of the fairy queen, if not of female fairies as a class. Her origins seem to be Elizabethan. In 1590 Edmond Spenser made his Faerie Queen a descendant of Titania, but the character was most explicitly and effectively introduced into fairy-lore by William Shakespeare in Midsummer night’s dream. She was not a traditional character of British folklore (as her name might, in any case, suggest) and the playwright was certainly very well aware of the British equivalent: Queen Mab features prominently in a famous speech by Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet, which was first performed in 1597. The Dream was written in 1605; did Shakespeare merely want a bit of variety or did he have other motives for creating a new faery monarch?

Diana

Somewhat like the name of her consort Oberon, Titania’s name is more descriptive than personal. ‘Titania’ simply means that she is born of Titans- though this naturally begs some very important questions. Roman writer Ovid tells us in The Metamorphoses that Titania is another name or aspect of the goddess Diana. The latter was the Roman deity responsible for childbirth and, as such, there are some parallels with Queen Mab the midwife. The Romans also linked Diana to the Greek goddess Artemis, who was primarily a goddess of nature, particularly of springs and water courses (she was, for example, known as Limnaia, ‘lady of the lake’, a name which for us now is freighted with resonances of Morgan le Fay and other fay maidens and such like nymphs). In her guise as goddess of woods and water, Artemis had obvious parallels with native nature spirits and the association makes considerable sense. However, Shakespeare had already used ‘Diana’ as a character in All’s well that ends well, five years previously to The dream, so perhaps again he merely sought variety- or had pursued the links even more deeply.

Edwin Landseer, Titania and Bottom, 1851

The Titans

Diana was descended from Titans, a heritage which takes us back to the roots of Greek mythology. The Titans were a race of giants born of Uranus and Ge (heaven and earth). Amongst their numbers were the male gods Oceanus, Cronus, Hyperion, Prometheus and Atlas; amongst the goddesses were numbered Thea, Phoebe and Rhea. The inter-relationships and identities of these beings are far from fixed in the myths, but we need not be concerned with the detail. It is the general tenor of the stories that’s significant: they contain a variety of fruitful themes and concepts.

Cronus is often seen as the chief of the Titans. He led a revolt against Zeus and the Olympian gods and was defeated and displaced, being banished with all his kind to imprisonment in Tartarus. It’s said that Cronus now sleeps eternally on some Western island, and as such his myth has very likely contributed to the growth of the story of King Arthur sleeping in Avalon. The sister of Cronus was Rhea, but she was also his wife and so mother of a pantheon including Zeus, Poseidon, Hera and others. In this role Rhea is commonly identified with another goddess, Cybele, who was in turn worshipped across the ancient world as the Great Mother Goddess. She is another deity of nature, fertility and wild places and, as such, fairly readily linked to a fairy queen of groves and springs.

The daughter of the famous Titan Atlas was the equally well-known Calypso, nymph of the island of Ogygia. It was she who detained Odysseus for seven years and tried to prevent him ever returning home with promises of immortality. The time-scale and the reward must trigger for us thoughts of detention in fairyland.

In summary then, these divine female Titans all have attributes and rich associations which provoke thoughts of British equivalents and which tie local beings into a wider and more powerful mythology. It may be for these reasons that Shakespeare chose the name Titania: she brought with her connotations of power and antiquity.

Shakespeare’s fairy queen

Rather like Artemis/ Diana, Shakespeare’s fairy queen is intimately associated with the natural environment. Her quarrel with Oberon disrupts the weather and the growing of the crops. This is summarised by Titania when she tells Bottom that:

“I am a spirit of no common rate./ The summer still doth tend upon my state.” (Act III, scene i)

She rules over the seasons and they follow her moods.

In due course, naturally, the character of Titania took on a life of her own. The name was taken up by others and became accepted as the appropriate appellation: for example, in Thomas Dekker’s play The whore of Babylon in 1607.

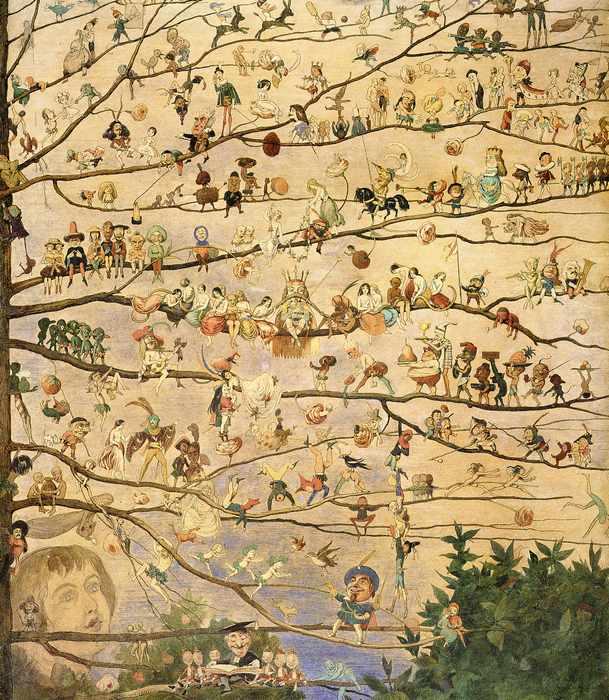

The new queen inherited much of the wanton sexuality of fairies generally and especially that of Queen Mab, giving us the erotically tinged imagery of Fuseli and Simmons as illustrated below. The buxom wenches of the paintings are ironic given the fact that Artemis, one of Titania’s forms, was also known as a goddess of chastity who was in conflict with Aphrodite (who, in fact, is also of Titan ancestry).

John Simmons, There sleeps Titania

Titania and Bottom c.1790 Henry Fuseli 1741-1825

Further reading

This posting was inspired by a reading of Geoffrey Ashe’s excellent Camelot and the vision of Albion. Robert Graves in The white goddess also has a good deal to say about Cronus and the rest. See too my consideration of the identity of Shakespeare’s Ariel.

An edited and expanded version of this post will be found in my books Who’s Who in Faeryland and Fayerie- Fairies and Fairyland in Tudor and Stuart Verse. See my books page for more information.