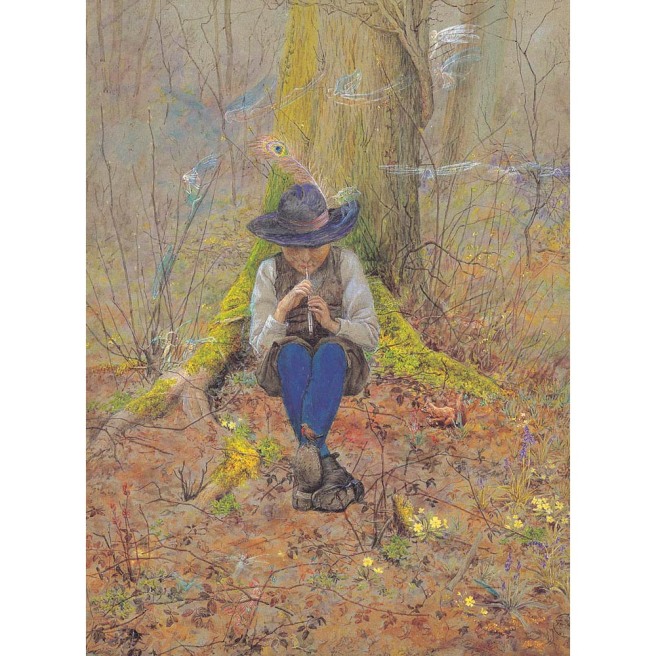

I have described before how fairy art made a contribution to the 1914-18 war effort, through artist Estella Canziani’s 1915 painting The Piper of Dreams, an image that became immensely popular amongst troops and their families. The Piper remains Canziani’s best known picture, but she had many other accomplishments and she painted several other faery scenes.

Canziani (1887-1964) was born in London, the daughter of painter Louisa Starr, who herself produced some ‘fantasy’ paintings, such as ‘A Fairy Tale’ in 1869 and ‘Undine’ the next year. Canziani lived her whole life in the same house, but she travelled extensively and published three travel books based on these trips. She was a painter, worked as a book illustrator and wrote articles in Folklore, the journal of the Folklore Society.

Canziani had started to paint The Piper of Dreams at Easter 1914, demonstrating that there was no thought on her part to produce an image that might cheer ‘our boys’ in the trenches with thoughts of home. Instead, it is a clear testament to the fact that she had inherited her mother’s interest in fantasy scenes. The picture’s original title was ‘Where the little things of the wood live unseen,’ nowhere near as emotive as the label it bore at the Royal Academy exhibition the next summer. The canvas sold the day the exhibition opened and hundreds of thousands of copies of the picture were sold over the next few years and posted to troops across the world.

In 1919 Canziani painted The Fairy of Childhood, which portrays a fae in a long red dress, seated on a tree stump, watching over a mother and baby who have fallen asleep in wild and lonely landscape. The fairy has red wings that fade to white towards the feather tips, making it look a good deal more like one of Fra Angelico’s angels, but there is a second, much smaller, blue sprite with wings sits on the ground in the foreground, perhaps confirming that we are witnessing a supernatural rather than heavenly scene. Other fairy pictures that Canziani painted include Fairies Bless the New-Born (see this posting for a reproduction of this), in which an armoured knight kneels before a stream or pool holding a naked baby whilst pale spirits arise from the water, and Dancing Sea Nymphs (1938) showing three naiads emerging from the surf on a beach, apparently celebrating the sunrise with music.

Perhaps rather more sinister is The Enchanted Basin, in which a boy and girl watch in wonder as another pale water sprite emerges from the surface of a pond chasing bubbles. My caution here comes not so much from the painting itself but from a wariness over fae water sprites, as I will describe in my forthcoming book Beyond Faery. Admittedly, the naiad here looks charming enough, but looks can be deceptive– especially where water is involved.

As mentioned, Canziani was also an illustrator and in 1923 she received a commission to work on an edition of Walter de la Mare’s Songs of Childhood. This incorporated several fairy plates: ‘Oh Dear Me!’ shows a little girl seated outside in a grassy place whilst fairies swirl around her; in ‘Down a Derry’ mermaids play instruments beneath the sea; ‘The Dwarf’ features a boy and a girl running along the ground as angel or fairy-like creatures with red wings soar away from them and, finally, in the plate for ‘Fairies Dancing’ a cloud of gauzy beings swarm in a woodland glade with a castle in the background.

The plates don’t quite match the poems for which they’re named. For instance, The Dwarf above seems to fit better with the verse titled The Gnomies:

‘Come away

Child and play,

Light wi’ the gnomies;

In a mound,

Green and round,

That’s where their home is!

We must also forgive de la Mare a truly terrible rhyme here. As for Oh Dear Me!, it seems to best be matched by Bluebells:

Where the bluebells and the wind are,

Fairies in a ring I spied,

And I heard a little linnet

Singing near beside.

Where the primrose and the dew are,

Soon were sped the fairies all:

Only now the green turf freshens,

And the linnets call.

Lastly, in the charming Good Morning (c.1931), another blonde-haired being in a red dress (this time with more definitely fairy wings of a gauzy, butterfly description) appears to a young girl. The child has poked her head out of the front window of her home, presumably attracted by the sound of the pipe that the fairy is playing; the girl now stares in utter amazement at the vision that has appeared in an ordinary city street. There’s a gentle humour to this vignette- something in the little girl’s posture I think- which contrasts with the sober scene of destitution and isolation that we see in The Fairy of Childhood.

Estella Canziani was not a truly great artist, but her pictures are bright and attractive. For further information about her and about twentieth century fairy art in general, see my book on the subject, Fairy Art of the Twentieth Century.