I’ve written previously about Rutland Boughton, the (original) Glastonbury Festival and the use of Arthurian and Faery themes in opera and song. Here I expand further on this theme within British classical music.

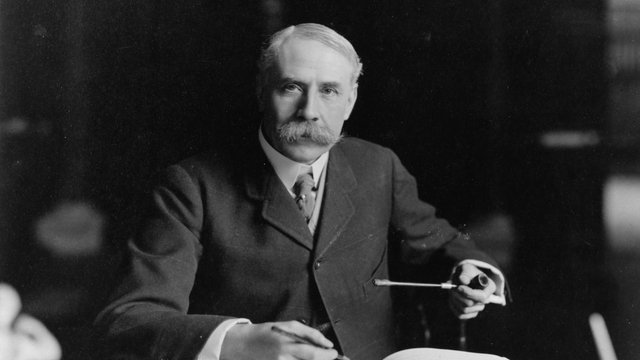

Arnold Bax

Arnold Bax (1883-1953) was a British composer for whom fairy and Celtic themes were of major significance. From his time as a student at the Royal Academy of Music between 1900 and 1905 Bax was greatly attracted to Ireland and Celtic folklore.

Bax & the Celtic Twilight

Soon after his graduation, Bax departed from classical influences and deliberately adopted what he conceived of as a Celtic idiom. His infatuation with the newly revived ‘Celtic’ culture, and with the island of Ireland, must be understood within the broader context of the fin-de-siècle artistic and spiritual fashions upon which the composer’s youthful imagination was nourished.

The latest aesthetic fashions tended to favour anything exotic and which contrasted with common-place concerns and the practicalities of everyday life. Theosophy, Eastern mysticism, French Symbolism and the spiritual Celticism that was so much in vogue in the 1890s all contributed important strands to the artistic culture of the time, while in the not too distant background was the Pre-Raphaelite medievalism of Rossetti and William Morris. There was much talk of neo-paganism and a strong interest in the occult. Undoubtedly, too, a large part of the general appeal of these subjects was that their potent atmosphere of sexuality. To this can be added, particularly for a musician, the impact of Wagnerian music drama, the daring novelties of Strauss and, a decade or so later, the lavish splendours of the Russian ballet.

Bax was intoxicated with all of this intellectual ferment and Celticism in particular dominated his imagination for a time and led directly to his fascination with Ireland. Even so, as we shall see, he remained equally susceptible to the exuberant and decadent poetry of Swinburne, and to the exotic influence of Russia. They were all just different aspects of the same extravagant sources of inspiration and they all left their mark on his music.

W.B. Yeats was, of course, the high priest of this Celticism and Bax duly came under his spell. In 1902, he says, he read The Wanderings of Usheen (Oisin), “and in a moment the Celt within me stood revealed.” In attempting to explain what he meant by this rhetorical phrase Bax has told us that, in his opinion, “the Celt- although he knew more clearly than most races the difference between dreams and reality- deliberately chose to follow the dream.” As there was “a tireless hunter of dreams” in his own make-up, Bax concluded that behind his everyday English exterior there must exist an inner Celtic self. His recognition of the true nature of this inner self, he insisted, he owed to Yeats. The poet’s influence was “the key that opened the gate of the Celtic wonderland to my wide-eyed youth,” and it was shortly after his first discovery of Niamh, Oisin and the enchanted islands in the western seas that Bax visited Ireland for the first time. The composer never doubted what the country had given him. If Yeats’ particular brand of Irish Celticism allowed Bax to focus his adolescent emotions , and to recognise what he believed was his ‘Celtic self,’ then the country itself provided him with a physical setting for his fantasies. “My dream became localised,” he said. Ireland represented that dream for him, although very evidently Bax saw the country through an idealistic haze:

“I went to Ireland as a boy of nineteen in great spiritual excitement and once there my existence was at first so unrelated to material actualities that I find it difficult to remember it in any clarity. I do not think I saw men and women passing me on the roads as real figures of flesh and blood; I looked through them back to their archetypes, and even Dublin itself seemed peopled by gods and heroic shapes from the past.”

Bax travelled extensively in the country and, for some years before the Great War, had homes both in England and in Ireland. So great was his identification with, and immersion in, the country and its cultural heritage that he even wrote Irish poetry under the pseudonym of Dermot O’Byrne. Bax’s brother also lived in Dublin during the period and through him the composer got to know mystic poet and painter AE (George Russell) and had contact with the city’s influential circle of Theosophists.

The result of this infatuation with Ireland can be heard in the music Bax composed during this phase of his life. “In part at least I rid myself of the sway of Wagner and Strauss,” he later said, “and began to write Irishly, using figures and melodies of a definitely Celtic curve,” although he never made any use of actual folk songs. The Irish influence is clear from the titles of works like A Connemara Revel (1904) and An Irish Overture (1905), while Cathleen-ni-Hoolihan, also of 1905, and Into the Twilight of 1908, clearly reflect his interest in Yeats. Nonetheless, despite his contact with, and sympathy for, the Gaelic-speaking population, his music always belonged to the “non-existent Ireland of the Celtic Twilight.”

For his first important work, A Celtic Song Cycle of 1904, Bax chose to set poems by the Scottish writer Fiona Macleod, and he produced about a dozen or so other songs to her verses in the years immediately following . Fiona Macleod was, after Yeats, the greatest populariser of Celticism at the end of the nineteenth century (readers may recall that Boughton was similarly influenced), even though the writing is now virtually unknown. Her work was arguably as much an inspiration for Bax at this period in his life as was the work of Yeats, although he never acknowledged this explicitly. As we’ve seen before, no such writer actually existed, because Fiona Macleod was in truth the Celtic alter ego of William Sharp, the Scottish literary critic, biographer and novelist. Bax met Sharp in due course and the influence of Sharp’s verse on the music he composed in the first decade of the century is very strong.

Fairy Music

In 1908 Bax began a working on trilogy of tone poems called Eire (Into the Twilight; In the Faëry Hills and Roscatha). A review of In the Faëry Hills in the Manchester Guardian said that “Mr Bax has happily suggested the appropriate atmosphere of mystery” and the Musical Times praised “a mystic glamour that could not fail to be felt by the listener.”

Into the Twilight began as life as a sketch for an orchestral interlude in Bax’s projected opera, Déirdre, based on the life of the tragic Irish heroine. Only the opening passages of Into the Twilight were actually newly written in 1908; much of the rest of the tone poem was a re-composition of one of Bax’s student works, Cathleen-ni-Hoolihan, which was composed between 1903 and 1905.

In the Faëry Hills, to which the composer gave the alternative Irish title An Sluagh Sidhe (The Fairy Host), was inspired by Yeat’s The Wanderings of Oisin. Bax wrote of the origin of the piece itself that “I got this mood under Mount Brandon with all W B [Yeats]’s magic about me – no credit to me of course because I was possessed by Kerry’s self”. He wrote in a programme note for the work that he had sought “to suggest the revelries of the ‘Hidden People’ in the inmost deeps and hollow hills of Ireland”.

In The Wanderings of Oisin the fairy princess Niamh falls in love with the Irish hero, Oisin, and his poetry, and persuades him to join her in the immortal islands. He sings to the immortals what he conceives to be a song of joy, but his audience finds mere earthly joy intolerable:

“But when I sang of human joy

A sorrow wrapped each merry face,

And, Patrick! by your beard, they wept,

Until one came, a tearful boy;

A sadder creature never stept

Than this strange human bard,” he cried;

And caught the silver harp away…”

The immortals then sweep Oisin into “a wild and sudden dance” that “mocked at Time and Fate and Chance”. The basic idea of a mortal being enticed away by supernatural forces is paralleled in several of Bax’s orchestral works of the same period, for example The Garden of Fand (1913-16) and in some Greek influenced works we shall now examine.

Pagan Music

Despite the importance of Yeats’ mystic and fairy poetry to Bax’s music, the influences the composer drew upon were actually much broader and deeper. His works are inspired by Irish and Arthurian myth, Scottish and Norse mythology, English folk tradition and by classical Greek legends. Indeed, Bax himself once scathingly dismissed the ‘Celtic twilight’ of the contemporary writers as “all bunk derived by English journalists from the spurious Ossian and the title of an early work by Yeats. Primitive Celtic colours are bright and jewelled.” He wanted to suggest that he was more interested in the raw, original sources than in modern imitations.

Bax’s pagan Greek influences are channelled through 19th-century English literature such as Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound and several works by Swinburne. The latter’s recreation of this pagan world introduced a fresh element of ecstasy into English poetry which obviously had an enormous appeal for Bax, whose own youthful outpourings, both musical and literary, were marked by their intense passion.

Another of Bax’s scores, The Happy Forest (1914), bears a title taken from a prose-poem by Herbert Farjeon which was itself influenced by the Idylls of Theocritus, known as the ‘father’ of Greek pastoral poetry. Bax used Farjeon as a point of departure for painting a musical impression of another enchanted wood filled with “the phantasmagoria of nature. Dryads, sylphs, fauns and satyrs abound- perhaps the goat-foot god may be there, but no man or woman.”

The most important of his scores from this time, Spring Fire (1913), was based largely on the first chorus of Algernon Swinburne’s Atalanta in Calydon, quotations from which appear at the head of each movement in the score. Completed at Tintagel and published in 1865, Swinburne’s poetic drama retold the Greek myth of the killing of the wild Calydonian boar by a band of heroes, that includes the huntress Atalanta. Bax was concerned with the earthier, primitive aspects of Greek mythology: the erotic capers of silvan demigods, the orgiastic frolics of the bacchantes and the followers of Pan, and the annual regeneration of nature.

Elemental phenomena- such as wild landscapes and seas- also had a very powerful effect upon him. His friend Mary Gleaves recalled that Bax had an “almost erotic” empathy with trees, and there are sexual connotations to his sea music as well. Bax himself acknowledged the non-Celtic nature of the ideas behind Spring Fire and the other scores and stated that ‘the true ecstasy of spring’ and the ‘affirmation of life’ were Hellenic concepts, foreign to the Celt: “Pan and Apollo, if ever they wandered so far from the Hesperidean garden as this icy Ierne, were banished at once in a reek of blood and mist and fire…”

These pagan scores date from the period just before the Great War, when there was a distinct artistic vogue for ‘pagan’ subjects. Nijinsky’s production of L’après-midi d’un faune was first performed in 1912, and The Rite of Spring in 1913. Other works of the period are Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé (1910) and Skryabin’s Prometheus (1913). Thus, in creating the finest of his pre-war compositions, Bax was not only embodying his own ‘adolescent dreams’ but responding to a broader trend.

Nympholepsy

The classical Greek influence is especially strong and relevant in one piece. Originally a work for solo piano, Nympholept was completed by Bax in July 1912. The title derives from Greek νυμφόληπτος (numpholēptos), one who suffers from nympholepsy, which is the state of rapture inspired by nymphs, and on the manuscript of the piece Bax wrote:

“The tale telleth how one walking at summer-dawn in haunted woods was beguiled by the nymphs, and, meshed in their shining and perilous dances, was rapt away for ever into the sunlight life of the wild-wood.”

The title was taken by Bax from a poem of 1894 by Algernon Swinburne, which describes a “perilous pagan enchantment haunting the midsummer forest.” In 1951, Bax further recorded that Swinburne’s poem was about the “panic induced by noonday silence in the woods.” There is indeed a fevered noonday atmosphere to the verse, with its invocations of Pan and the pulse of being pervading everything:

“In the naked and nymph-like feet of the dawn… / And in each life living, O thou the God who art all.”

The manuscript of the orchestral version has an additional note by Bax, a quotation from George Meredith’s poem The Woods of Westermain, which conjures up further images of the goddess, imps and enchantment:

“Enter these enchanted woods/ You who dare…”

Robert Browning also wrote a poem entitled Numpholeptos, and Bax himself had written one called Nympholept, which is dated 26th February 1912- five months before the piano score was completed. It was eventually published by him anonymously in Love Poems of a Musician (London, 1923) and tells how the narrator “chased all day the elfin bride” through a forest. Browning too asks “What fairy track do I explore?” in his description of his obsessive love. The equation between classical nymphs and native fairies is one that has been made since Tudor times, meaning that, in literary and musical terms, the terms can be interchangeable.

Regrettably, Bax’s optimistic yearning for an imaginary Arcadian existence (what he dismissed as “the ivory tower of my youth” in 1949) was soon to be swept away by the harsh realities of the The Great War, the Easter Rising in Ireland and, on a more personal level, the disintegration of his marriage. Never again in his music was Bax to visit the world of classical antiquity, or to recapture the mood of unadulterated happiness and elation.

An extended discussion of the condition of nympholepsy is to be found on my Nymphology blog.

John Ireland

For Arnold Bax, the love of myth and fairy lore was an intellectual matter; for fellow composer John Ireland (1869- 1962) it was real and physical, the product of personal sensation and experience. He once declared of himself: “I am a Pagan. A Pagan I was born and a Pagan I shall remain- that is the foundation of religion.”

Arthur Machen

“They told me Pan was dead, but I,

Oft marvelled who it was that sang

Down the green valleys languidly

Where the grey elder thickets hang…”

A key factor in Ireland’s philosophy and music was the writing of Welsh novelist, Arthur Machen. The composer first came across his work when he picked up a copy of The House of Souls at Preston railway station in 1906. He said that he instantly bought it and instantly loved it: its impact upon him was as important as had been reading De Quincey’s Confessions of an Opium Eater.

Nearly thirty years later Ireland was to get to know Machen personally, but the author’s world of fantasy and mystery had had an immediate effect upon him. Machen’s books have been described as a “catalyst” for Ireland, something which “infused” his compositions. He himself declared that his music could not be understood unless the listener had also read Machen’s stories.

For Ireland, Machen had the status of a “seer.” The composer’s interest in magic and the unknown were ignited by reading his stories and he shared with the author a belief in the subconscious or ‘racial memory,’ the idea that through ancient sites such as barrows and standing stones he could connect to an ancient mysticism. At Chanctonbury Ring and Maiden Castle hillforts, for example, Ireland believed that he could still detect traces of the early rites that had been performed there.

Ireland was especially fascinated by ritual and by the occult. He shared this, too, with Machen, who was a member of the Golden Dawn along with Yeats, Aleister Crowley, Bram Stoker and fellow fantasy novelist Algernon Blackwood. Ireland’s particular devotion was to Pan. In 1952 he said that:

“The Great God Pan has departed from this planet, driven hence by the mastery of the material and the machine over mankind.”

The composer was not alone in this fascination (as we have already seen from Arnold Bax). From the 1880s until the 1940s there was something of an artistic cult for the ancient god, as is witnessed in poetry (Walter de la Mare’s They told me (see above) and Sorcery, Swinburne’s Palace of Pan, Robert Browning’s Pan and Luna and Elizabeth Browning’s A Musical Instrument) and in novels (such works as Francis Bourdillon’s A Lost God, E. F. Benson’s The Man Who Went Too Far and Saki’s The Music on the Hill.) Aleister Crowley wrote a ‘Hymn to Pan’ and the rural god even appears in Kenneth Graham’s Wind in the Willows, in the chapter entitled ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ (later the title of an album by Pink Floyd). Pan had an aura of decadence and Ireland was definitely attracted to the god’s darker side- the very same aspect that was celebrated by Machen.

Arthur Machen was not, of course, John Ireland’s sole influence. He drew musically upon the spirit of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and he also found John Brand’s Observations on Popular Antiquities, a rich source of English fairy lore and folk tradition, a further valuable inspiration. The fairy author, Sylvia Townsend Warner, who happened also to be a relative of Machen, was another influence, her concerns with physical and mental ecstasy matching Ireland’s own.

The Hill of Dreams

Ireland found Machen’s novel The Hill of Dreams intensely compelling and reckoned that it deserved a place in the ‘literary hierarchy.’ It never ceased to be a source of inspiration for him. It is the strange story of a young man who seems to come into contact with an ancient cult at an overgrown hill fort and who is eventually claimed by the satyrs and witches who haunt the place. The book probably helped shape Ireland’s piano concerto, Mai-Dun, which takes its title from the name Thomas Hardy used for Maiden Castle.

The mood of intoxicating summer heat, fevered sexual dreams and pagan mystery invoked here are exactly what Bax was trying to emulate in Nympholept.

Graham Ovenden, The White People

The White People

“What voice is that I hear,

Crying across the pool?

It is the voice of Pan you hear,

Crying his sorceries shrill and clear”

Walter de la Mare, Sorcery

One of the stories in Machen’s House of Souls is the remarkable White People, an account by a young girl of her encounters with mysterious white people (who may be fairies), her discovery of a lost altar to Pan and the revelation of hidden mysteries to her by water nymphs, fae spirits who may seem charming and harmless in some aspects, but fierce in others (see Bax earlier). Ireland said that this haunting story had “astounding qualities” at which he “never ceased to marvel.”

The story directly inspired three very short piano suites written in 1913 by Ireland, Island Spell, Moon-Glade and Scarlet Ceremonies, which he grouped together under the title Decorations. Scarlet Ceremonies took its title directly from The White People. Two of its movements are headed by citations from poet Arthur Symons; for example, Island Spell begins:

“I would wash the dust of the world in a soft green flood,

Here, between sea and sea in the fairy wood,

I have found a delicate, wave-green solitude…”

The third song borrows some lines from Machen:

“Then there are the ceremonies, which are all of them important, but some are more delightful than others: there are White Ceremonies, and the Green Ceremonies, and the Scarlet Ceremonies. The Scarlet Ceremonies are the best…”

Ireland’s fascination with pagan ritual is also demonstrated by 1913’s brief prelude for orchestra, Forgotten Rite, a composition that has been said to be permeated with Machen’s notion of a “world beyond the walls;” with the proximity of the supernatural. The Rite was particularly inspired by the ancient landscapes of Guernsey, an island that Ireland described as being especially ‘Machenish,’ and it also invokes Pan. In Sarnia (1940) Ireland pursued this theme, celebrating the ecstasy of communing with nature. This ‘Island Sequence’ comprises three piano pieces, ‘Le Catioroc’ (a Guernsey headland crowned by the impressive Le Trepied dolmen), ‘In a May Morning’ and ‘Song of the Springtides,’ the being latter prefaced by a quotation from Swinburne. The ritualistic mood again derives from Machen’s novel The Great God Pan.

Le Trepied

John Ireland and the Fairies

As I stated earlier, Ireland’s pagan and mystic fascinations came not just from reading (unlike Bax). He lived his occult and faery beliefs.

In 1933 John Ireland was visiting the South Downs in Sussex. He was working on a new composition and walked high up on top the Downs to visit a ruined chapel called Friday’s Church. Ireland was irritated to find that he was not alone. A group of children dressed in white appeared near him and started to dance. He watched them for some time before it began to dawn upon him that the infants made no sound and their feet upon the turf were silent. He looked away, briefly distracted, and when he looked back- they had vanished. He was convinced that he had had a fairy experience. He wrote about it in detail to Machen, whose laconic reply was:

“Oh, so you’ve seen them too?”

Ireland’s piano concerto Legend was the product of this experience.

In conclusion

As I’ve suggested before, the impact of the fairy faith upon British culture is deep and persistent: it’s given rise to musicals, operas, epic novels and to plays. All I can do, finally, is to encourage readers to go to the works of art themselves. Read Machen and Macleod, read Blackwood and Swinburne; try the compositions of Bax and Ireland. Sylvia Townsend Warner’s book of her own fairy tales, Kingdoms of Elfin, is also very entertaining.

For more on the influences of Faery on both classical and rock music, see my 2022 book The Faery Faith in British Music which is available from Amazon, either as an e-book (£5.95) or a paperback (£7.95).