As has been discussed in previous posts, the residents of fairyland were conceived to spend a good deal of their time tormenting humans, either maliciously or mischievously, some in thievery from hapless mortals and a little in honest commerce. The impression gained from folklore though, is that mostly the fairy life was one of leisure, with nothing to do but have fun.

Again and again the sources connect the fairies with pleasure and revelry, and in particular:

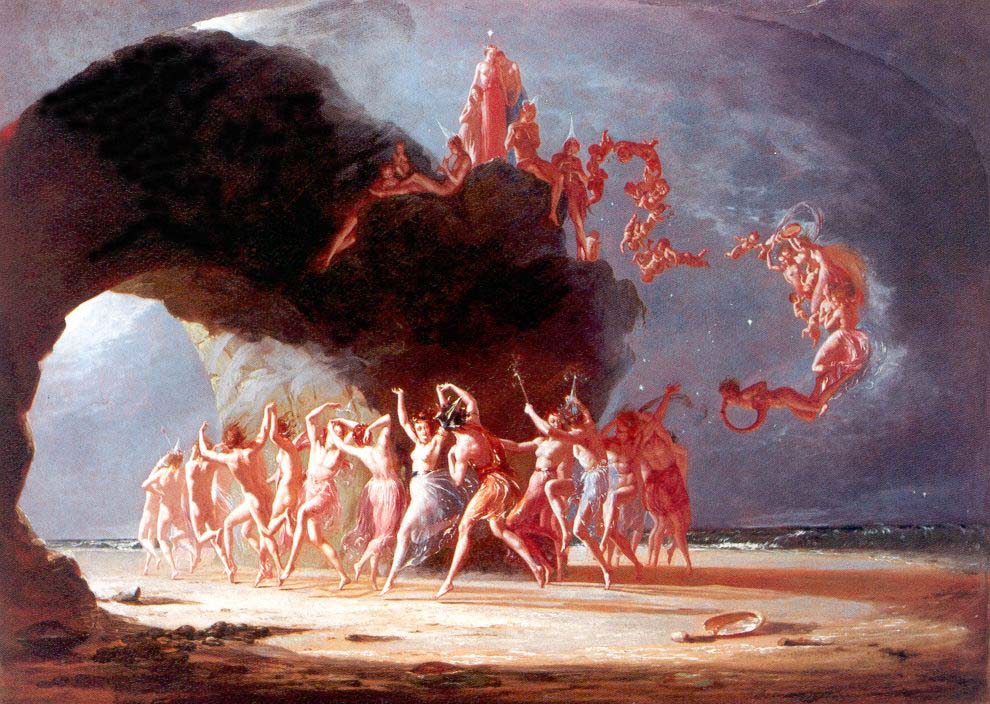

- dancing appears to have been their chiefest delight and one of their commonest attributes (for example, see Macbeth, IV, 1- “Like elves and fairies in a ring.”). Most often this is said to take place by moonlight and usually in open places- in grassy fields, meadows, pastures and near megalithic monuments. The fondness for moonlight is a widespread preference recorded in literature, including Milton in Comus- “Now to the moon in wavering morrice move…” (lines 115-117), Lyly, Fletcher and, of course, Shakespeare, who mentions ‘moonshine revels’ in both Midsummer Night’s Dream (II, 2) and The Merry Wives of Windsor (V, 5). In Cornwall fairies are said to dance at their fairs, although again these are most likely to be held in open spaces (Wentz p.171). The dances would invariably be in a circle, in one late nineteenth century case on the Isle of Skye being around a bonfire (see Briggs, Fairies in tradition p.20), and the inevitable consequence of this was the well-known ‘fairy rings’ on the grass. This is noted by Prospero in The Tempest (V, 1) who invokes “Ye elves … that/ By moonshine do the green-sour ringlets make/ Whereof the ewe not bites.” Many other writers also allude to the same habit and phenomenon, including Ben Jonson, Lyly, Milton, Brown, John Aubrey and Thomas Nashe. Wirt Sikes in British goblins was told that the fairies prefer (reasonably enough) to dance in dry places, preferentially under oak trees; there they leave reddish circles- most often under the female oaks (p.106). Humans might be lured to join these ‘wanton’ dances and would have great trouble escaping, as I have described before.

- “Most dainty music”- music naturally accompanied the dancing, both instrumental and vocal; for example Thomas Brown in The Shepherd’s pipe describes fairies dancing to piping in meadows or in fields of yellow box. In Scotland the bagpipes appear to have been preferred. John Dunbar of Invereen told Wentz’ informants that the sidh were “awful for the bagpipes” and often were heard playing them (p.95). Fairies are frequently associated with particular pipes and chanters in the Highlands (Wentz pp.86 & 111) and it is also notable that their musical skills might be bestowed upon fortunate humans (p.103). Equally, it is said, several folk tunes are originally fairy airs, heard and memorised by attentive players. To human ears the fairy music was invariably found to be ‘soft and sweet’ and nearly irresistible- especially to the young (Rhys pp.53, 86, 96 & 111; Wentz p.159). Throughout Shakespeare’s Tempest “heavenly music” is a central element to the enchantments used by Prospero and Ariel, lending it a magical as well as pleasurable aspect. Humans, it seems, are welcome to join in fairy songs (just as with dances) so long as they are polite and, possibly even more importantly, musical, so that their contribution is harmonious and positive. Woe betide the poor vocalist: in one Scottish case a hump back who sang well and enhanced a song was rewarded by having his hump taken away; a jealous imitator who tried to repeat this spoiled the rhyme and was punished by bestowal of the hump (Wentz p.92);

- feasting too went along with the the enjoyment of song and dance. Banqueting, wine and ale are frequently alluded to (in the Cornish stories of Selena Moor and Miser on the Gump, for instance). A Zennor girl came upon pixy ‘junketting’ in an orchard near Newlyn, Wentz was told (p.175). In many of the instances when fairy hills are seen to open up it is to reveal a fine feast within (for example William of Newborough, Book I, c.28 & Keightley p.283).

- riding provided the other major pastime. The ‘fairy rade’ or procession features in a large number of stories, for example Allison Gross and Tam Lin. These processions are described as being richly caparisoned and very stately. Mounted fairies also liked to hunt, although these outings tend to be far noisier and wilder affairs. We are never surely told what is was that the fairies preferred to chase, but we often hear of their abandoned gallops across the countryside with their hounds.

- mischief might also be said to be a fairy entertainment. The taunting of humans is a fixed fairy character trait and was a primary source of pleasure for several types of fairy- especially the pucks and hobgoblins, and this is exemplified by Thomas Haywood in his Hierarchie of the blessed angels (1636, p.574) when he describes how they enjoy gambolling at night on a household’s shelves and settles, making a noise with the pots and pans and waking up the sleeping inhabitants.

In all of the above, it will be noted, the fairies mirrored the activities of earthly royal courts and noble houses. At the end of Midsummer Night’s Dream, for example, we are told that Oberon “doth keep his revels here tonight.” Overall, in fact, the strong impression gained from a study of the accounts (both traditional and literary) is that the fairies’ time was mainly filled with pleasure and mischief, and that there was only a very a scanty ‘work ethic.’ This is echoed in a comment on the Anglesey fairies recorded by one of Evans Wentz’ interviewees. The woman observed with some disapproval that “all the good they ever did was singing and dancing.”

‘When the fairies came,’ Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, 1888- 1960

An expanded version of this posting is found in my book British fairies (2017). I have returned to fairy music and song in a later post. See too my 2023 book, ‘No Earthly Sounds- Faery Music, Song & Verse,’ which is available as an e-book and paperback from Amazon/ KDP.