In a book published in 2017, American art historian Susan Casteras contributed a chapter on Victorian fairy painting. She perceptively remarked how nudity, which is very far from being an inherent element in folklore, became something that the Victorians chose to exaggerate in their visions of fairyland. Many paintings of the period, she rightly observed, were all about “flaunting nudity for its own sake rather than as a supposedly accurate transcription of faery lore.” (S. Casteras, ‘Winged Fantasies: Constructions of Childhood, Adolescence and Sexuality in Victorian Fairy Painting’ in Marilyn Brown, Picturing Children, 2017, c.8, 127-8)

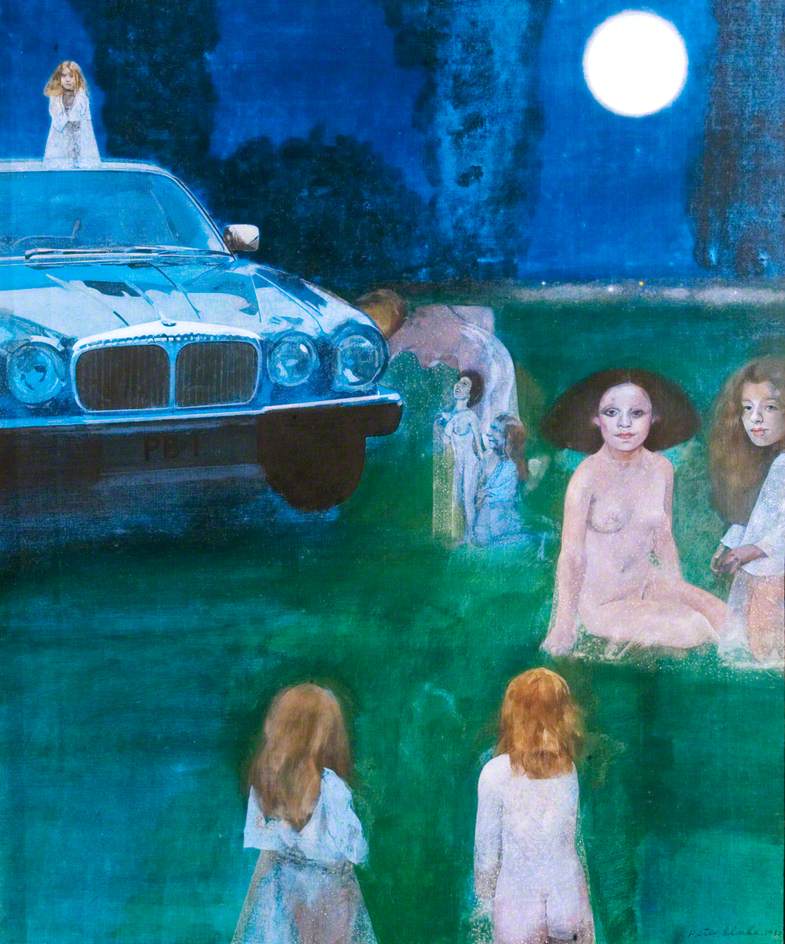

Looking at John Simmons’ painting above, you cannot help but agree with the second part of Casteras’ comment- although Simmons was a particular offender, producing a number of ‘pin-up’ canvases. What about the folklore evidence, though? Victorian pictures- and more recently the work of Alan Lee, Brian Froud and Peter Blake– have habituated us to the idea of a Faery full of frolicking nudes, but how traditional is this?

The honest answer has to be that there’s very little sign of nudity in the older accounts of Faery. In my post on fairy abductions of children, I mentioned the story of a girl who temporarily went missing in Devon. A game keeper and his wife living at Chudleigh, on Dartmoor, had two children, and one morning the eldest girl went out to play while her mother dressed her baby sister. In due course, the parents realised that the older child had disappeared and several days of frantic and fruitless searching followed. Eventually, after hope had nearly been lost, the girl was found quite near to her home, completely undressed and without her clothes, but well and happy, not at all starved, and playing contentedly with her toes. The pixies were supposed to have stolen the child, but to have cared for her and returned her.

Now, this girl was a human infant and there may have been several reasons why the pixies might have taken off all her clothes. They may have objected to human things; they may have thought a ‘natural’ state was healthier and preferable. Whatever the exact explanation, it’s one of the few instances where there’s a suggestion that nudity might be the normal condition in Faery.

A calendar illustration by Mabel Rollins Harris

The other evidence is all qualified in one way or another. Mermaids don’t have clothes, but that’s for very obvious reasons. Men are forever falling in love at first sight with these creatures, but you may well suspect that coming across a uninhibited and naked female is a pretty strong draw in any case.

Some fairies don’t ‘need’ clothes at all because they’re naturally very hairy: the brownies, hobgoblins and the Manx fynoderee are all examples of these. Their shaggy pelts were covering enough. It’s almost always this kind of faery that is the subject of a story in which a reward of clothes for services rendered alienates the helpful being. Typically, a brownie or boggart with work faithfully on a farm, threshing grain, carrying hay and tending the livestock, all for very little reward except some bread and milk left out ta night. After a while, the curiosity of the farmer overcomes good sense and the creature’s labours are spied upon. It’s seen to be (at the very best), dressed in tattered rags and (at the worst) completely naked. Pity is taken and new clothes are made in recognition of its hardwork, but all that’s achieved is to offend the fae, who recites a short verse- and leaves forever.

Lastly, the only other definite example of bare fairy flesh is one I’ve discussed several times previously and one in which ulterior motives are very important. In the medieval romance of Sir Launval, the young knight is summoned into the presence of the fairy lady, Tryamour. She’s found in a pavilion in a forest, relaxing on a couch on a hot summer’s day.

“For hete her clothes down sche dede/ Almest to her gerdyl stede,/ Than lay sche uncovert; Sche was as whyt as lylye yn May, / Or snow that sneweth yn wynterys day, / He segh never non so pert.””

“because of the heat, she’d undone her dress nearly to her waist; she lay uncovered; she was as white as a lily in May, or snow falling on a winter’s day; he’d never seen anyone so pert.”

Tryamour’s plan is to seduce Launval and, plainly, lying there topless and available is a pretty good scheme for winning his attention. It’s not normal behaviour in Faery, though, anymore than it is on the earth surface. Most of the accounts we have of the appearance of fairies describe their clothes– their style and their colour; we are not told that they are provocatively naked.

Nude fairies, therefore, seem to be a Victorian obsession; they are the soft porn of their day. As has been described before, it was acceptable to display bare breasts in art, but only so long as it was justifiable and/ or distant from the present day. Painting classical nymphs, oriental harems and fairyland let artists get away with it. they seized the opportunity- regardless of the fact that the folklore provided almost no basis for this.