In this post I return once again to the subject of fairy rings. I add a little more factual and folklore information to what I’ve written before and then turn to consider how popular twentieth century art has chosen to represent rings.

Fungi & Fairies

The origins of fairy rings were extensively debated in the late eighteenth century. The Gentleman’s Magazine, for a decade from 1788, carried an exchange of correspondence in which readers described and theorised about these curious features in their landscape. Charles Broughton, writing in 1788, remarked upon the semi-circular marks that appeared consistently in his pasture land. They had a base of about four yards, he reported, and were half a yard thick (across their width). Another writer (‘JM’) in 1790 described the circles that appeared in the meadow-land near his home. They were 6-8 inches broad with a diameter of six to twelve feet and were covered in champignon mushrooms. He noted that the land hadn’t been ploughed for 19 years and that the cattle were turned in annually to eat the aftermath (the stubble left after cutting the hay). Another letter from 1792 remarked upon the many large fairy rings to be seen in the meadows between Islington and Canonbury, north of London. The present day inhabitant of the capital will smile wryly over this, as the area is now overlain by Georgian squares and terraces, built not too long after the letter was written.

Both the writers just named ascribed the rings to mushrooms, but subsequent correspondents blamed the effect of horse dung, moles, lightning and, even, the Ancient Britons, who had dug defensive trenches on the sites. What we can tell, certainly, is that these very noticeable features in the landscape excited public interest and speculation because they were so common and so distinctive.

Folklore

The learned gentlemen musing on the formation of the rings all dismissed the fairies as a cause, naturally. Nonetheless, for generations it had been well-known that the Good Folk were in fact the makers of the marks. In Devon it was said to be the hoof-marks of ponies that the fairies rode round and round in circles at night that made the circles; generally though, across Britain, it was the action of dancing feet that was blamed. For instance, Evans-Wentz (Fairy Faith p.181) was told about a spot near St Just in the far west of Cornwall, called Sea-View Green, where the piskies could regularly be seen dancing on moonlit nights, looking like little children dressed in red cloaks. Another witness told Evans Wentz that the piskies preferred to ‘play’ in marshy locations and that these round places were locally called ‘pisky beds’ (p.184).

The rings were dangerous places, that was for sure. Dew should not be gathered from them (as was sometimes done to improve the complexion) and the faes would counteract any magical quality it possessed anyway. Anyone who stepped accidentally into a ring could be abducted by the fairies. Great fear about this danger was instilled by parents into children, who retained the dread into their own adult years (see, for example, Wirt Sikes, British Goblins, p.103 for just such a warning from an old Glamorganshire man and also Evans Wentz, Fairy Faith, p.91). The rings might be a place to which a person was ‘pixy-led’ and then trapped, as was recounted in the story of Einion ac Olwen (Evans Wentz p.161). The same story notes the distinctiveness of ring too: “a hollow place surrounded by rushes where he saw a number of round rings.”

Twentieth Century Popular Art

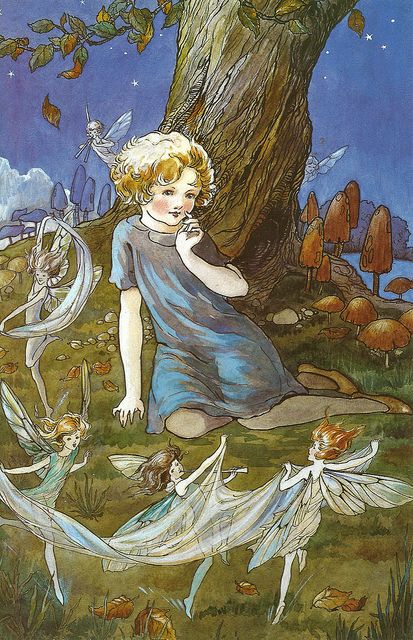

The consensus was that, for many reasons, fairy rings were perilous places. The best thing was to avoid and respect them. However, a child would never have learned that serious lesson from the pictures aimed at them in the early twentieth century. The illustrators of children’s books, as well as printed ephemera such as postcards and greetings cards, all used toadstools as a convenient signifier of the presence of magical beings in their scenes and treated fairy rings- and their occupants- as benign and friendly beings, who only wished to play and dance with children. Many of the most significant faery artists of the period, such as Margaret Tarrant, Hester Margetson and Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, propagated this simpler and happier version of Faery. The Good Folk themselves were reduced to girly winged fairies in dresses and cheeky pixies/ elves in pointed hats and almost all the complexity, peril and moral ambiguity of traditional faery lore was effaced. Their pictures (and the whole race of flower fairies) remain attractive art even today, but as a guide to folk belief they are misleading.

Further Reading

See my recently released book, Faery, for more discussion of fairy rings and other fairy places. For more on the art of Faery, see my book Fairy Art of the Twentieth Century

And lastly, a cigarette card from W D and H O Wills’ Cigarettes:

For more on faery rings and the faeries’ interactions with nature, see my book Faeries and the Natural World (2021):