The poet Andrew Young (1885-1971), wrote this evocation of A Prehistoric Camp, :

“It was the time of year

Pale lambs leap with thick leggings on

Over small hills that are not there,

That I climbed Eggardon…But there on the hill-crest,

Where only larks or stars look down,

Earthworks exposed a vaster nest,

Its race of men long flown.”

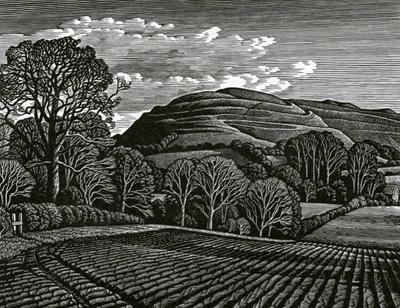

Eggardon Hill, which is east of Bridport, in Dorset, is an Iron Age hill fort, but there is evidence of much earlier use in the form of several tumuli or long barrows on its summit. The presence of barrows within the defences is what interests me here: it is quite a common feature, as for example at Hambledon Hill further east in the same county.

Also by Young is the poem ‘Wiltshire Downs‘ from which I quote the final stanza.

“And one tree-crowned long barrow

Stretched like a sow that has brought forth her farrow

Hides a king’s bones

Lying like broken sticks among the stones.”

With his mentions of lost races and ancient kings, Young has connected to a key feature of our landscape and folklore, but he does not take advantage of the full mystery associated with these features. There are deep resonances here at which Young only hints in the most subtle, or oblique, manner. Welsh poet and artist David Jones made full use of the layers of tradition and myth, though, in his extended prose-poem concerning the Great War, In Parenthesis (1931), in which he described slumbering British troops in Flanders dugouts as being “like long-barrow sleepers, their dark arms at reach.” He returned to this theme decades later in his series of poems, The Anathemata. In the poem Sherthursday and Venus day Jones mentioned “the hidden lords in the West-tumulus.” In the same poem he also recognised the intriguing mystery of hill-forts as well as barrows, imagining a climb “up by the parched concentric bends over the carious demarcations between the tawny ramps and the gone-fallow lynchets, into the vision lands.”

“Into the vision lands…” Jones intimately knew and worked with the legend and myth of the British Isles: he understood that the landscape was more than topography, that it comprised accrued memories and stories, that our reading of the land is as much composed of (often subconscious) echoes of legend and fairy-tale as it is of geology and land use. Beneath the features we see there are, indeed, the “hidden lords,” the “long-barrow sleepers” of British tradition. King Arthur sleeps beneath a hill, somewhere, waiting to answer the call to save Britain. Places across the British Isles are charged with the power of these genii loci, the spirits of place.

Rudyard Kipling was another writer who drew on the deep wells of folklore and, in his poem ‘Song of the Men’s Side’ from the book Rewards and Fairies, he advised:

“Tell it to the Barrows of the Dead—run ahead!

Shout it so the Women’s Side can hear!

This is the Buyer of the Blade—be afraid!

This is the great God Tyr!”

In Kipling’s story The Knife and Naked Chalk the faery Puck, the archetypal British supernatural being, introduces the children Dan and Una to a neolithic herder who tells a tale of “a Priestess walking to the Barrows of the Dead.” The herder sees a girl he knows at a tribal ceremony:

“I looked for my Maiden among the Priestesses. She looked at me, but she did not smile. She made the sign to me that our Priestesses must make when they sacrifice to the Old Dead in the Barrows. I would have spoken, but my Mother’s brother made himself my Mouth, as though I had been one of the Old Dead in the Barrows for whom our Priests speak to the people on Midsummer Mornings.”

The ancestors lie beneath the tumuli and their purpose is to advise and help their living descendants. Perhaps that function is not yet exhausted…

As just mentioned, a vital element of one strand of British folk stories (the so-called ‘Matter of Britain’) is the concept of the sleeping hero. King Arthur, most commonly, is understood not to be dead and buried in Avalon but lies hidden beneath some ancient feature- a hill fort or cave, perhaps- awaiting the time when he is summoned to bring salvation to the island and its people. Beneath the ancient heights of those tribal fortifications, warriors lie in wrapped in the dreams of centuries, patiently biding their time until the call is sounded and their slumbers are ended. Arthur’s the best known of these heroes, but other sleepers include Thomas of Erceldoune, or Thomas the Rhymer, the mortal man who met the faery queen one May Day and travelled with her as her lover into Faery. Now he serves the once and future king, awaiting the day. Faery and folk history become entwined; Arthur is both mortal warrior and immortal faery monarch; human politics merge with mystical meaning and leave their mark upon the land- a constant reminder, to those in the know, that there is more present than meets the eye.

In another of his poems, Rite and Fore-time in the collection Anathemata, David Jones equated tumuli with altars, regarding both as places of worship and of burial of holy relics. His analogy is perceptive and powerful. The sleepers in the barrows are our ancestors, our predecessors on the land, and doubtless one element in their interment and the rites associated with their monuments was a reassertion of community links not only with those who had gone before but also with the landscape over which their remains now watched. They had become both features in the landscape and guardians of that landscape.

In my 2022 book The Spirits of the Land- Faeries and the Soul of Britain, I pursue these themes in more detail, examining how the faeries as spirits of place and the stories of Arthur have become woven into the archaeology, the place-names and landforms of the country.

8 thoughts on “Like long barrow sleepers”