John Duncan, The riders of the sidhe

“I speke of manye hundred yeres ago.

But now kan no man se none elves mo…”

(Chaucer, Wife of Bath’s Tale)

An abiding aspect of accounts of Faery is that the fairies aren’t around anymore and that fairy belief is fading; it was once strong, but not any more. This sort of account has been given repeatedly for the last five hundred years or so. Fairy-lore expert Katherine Briggs to some extent subscribed to this view when she called her 1978 book The vanishing people, although she herself collected some modern modern sightings as well.

Fairies have always been going, but they have never finally and completely gone. In Farewell to the fairies, the final chapter of her book Strange and secret people- fairies and the Victorian subconscious, Carole Silver observed that:

“The fairies have been leaving England since the fourteenth century but have never quite left despite the rise of the towns, science, factories and changes of religion.”

Two processes were believed to be working in parallel. There was an active departure of the fairies combined with a growing disbelief amongst the human population. Combined, these factors convinced observers again and again that our good neighbours had deserted us. Sometimes the departure was the the fairies moving away from a vicinity, other times it appears that they were vanishing completely.

“Robin Goodfellow is a knave”- the sixteenth century & before

Chaucer was the first to declare that the fays had disappeared, and there has been a constant chorus of lamenting voices ever since. These were strengthened, from the mid-sixteenth century onwards, by a belief that it was the Reformation which had driven out the supernaturals, the fairies’ Christian faith being inimical to that of Luther and Calvin.

By the late sixteenth century Reginald Scot felt able to declare that “Robin Goodfellow ceaseth now to be much feared.” Elsewhere in The discovery of witchcraft he noted that “By this time all Kentish men know (a few fooles excepted) that Robin Goodfellow is a knave.” In 1591 George Chapman had a character in his play A humorous day’s mirth query whether “fairies haunt the holy greene, as ever mine auncesters have thought.” The fairy faith was increasingly seen as a thing of the past, or at the very least as a matter for an older generation and for less well educated and more superstitious folk. For instance, writing in 1639, Robert Willis described how-

“within a few daies after my birth… I was taken out of the bed from [my mother’s] side and by my sudden and fierce crying recovered again, being found sticking between the beds-head and the wall and, if I had not cried in that manner as I did, our gossips had a conceit that I had been carried away by the Fairies…” (Mount Tabor p.92)

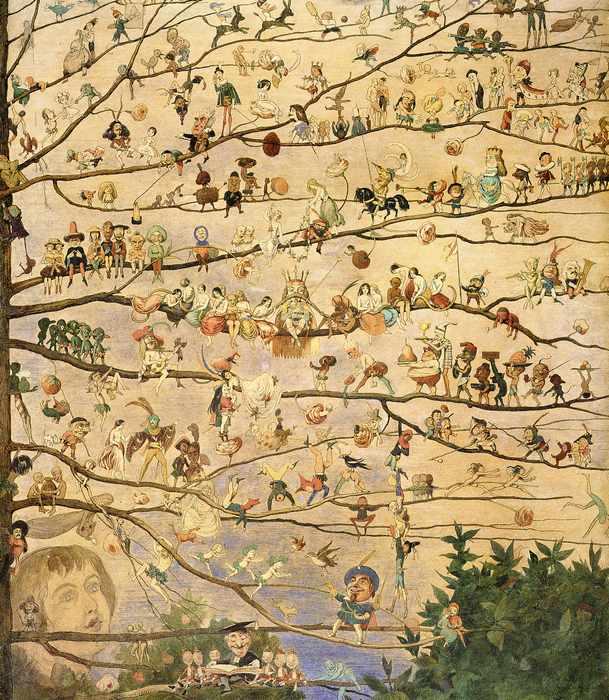

Richard Doyle, The triumphant march of the elf king, 1870

“Out of date and out of credit”- the 1600s & 1700s

These early sources would suggest that fairy belief was over and done with by the start of the seventeenth century. That was far from being the case. As late as 1669, it seems, a spirit called ‘Ly Erg’ had haunted Glen More in the Highlands. Describing the Hebrides in 1716, Martin Martin averred that “it is not long since every Family of any considerable Substance in these Islands was haunted by a Spirit they called Browny…” Speaking of Northumberland in 1729 the Reverend John Horsley felt that “stories of fairies now seem to be much worn, both out of date and out of credit.” In 1779 the Reverend Edmund Jones alleged that, in the parish of Aberystruth, the apparitions of fairies had “very much ceased,” although the tylwyth teg had once been very familiar to the local people. In other words, there had been belief but it was dwindling, or had died out.

“A winter evening’s tale”

The fairy faith was still apparently on the wane, or only just faded, during the next century too. This was particularly believed to be the case in Scotland. Shepherd poet James Hogg described the experiences of William Laidlawe, also called Will O’Phaup, who had been born in 1691 and who was “the last man of this wild region who heard, saw and conversed with the fairies; and that not once but at sundry times and seasons.” Will lived on the edge of Ettrick Forest which was “the last retreat of the spirits of the glen, before taking their final leave of the land of their love…” The fays’ departure was a regular theme for Hogg. For example, in The queen’s wake he claimed that “The fairies have now totally disappeared… There are only a very few now remaining alive who have ever seen them.” In 1820 Sir Walter Scott announced that “The fairies have abandoned their moonlight turf.” Writing of the Tay basin in 1831 James Knox agreed that “during the last century the fairy superstition lost ground rapidly and, even by the ignorant, elves are no longer regarded, though they are the subject of a winter evening’s tale.”

In a description of the Highlands in 1823 it was said that brownies had become rare, but that once every family of rank had had one. Likewise Alan Cunningham, a lowland Scot, said that in Nithsdale and Galloway “there are few old people who have not a powerful belief in the influence and dominion of the fairies…” Several accounts of the fairies’ departure from the Scottish Highlands can be dated to about 1790, although a lingering faith persisted with some into the middle of the next century. A Galloway road-mender refused to fell a local fairy thorn in 1850, for example.

Also in the early 1820s, the fairies of the Lake District were declared extinct. Further south still, but at almost the same time, Fortescue Hitchens pronounced that in Cornwall-

“the age of the piskays, like that of chivalry, is gone. There is perhaps hardly a house they are reputed to visit… The fields and lanes are forsaken.”

John Anster Fitzgerald, A halt in the fairy procession

“Credulous times”?- vanishing Victorian fays

Of Northamptonshire in 1851 it was said that “the fairy faith still lingers, but is in the last stages of decay.” Nevertheless in 1867 John Harland could write that “the elves or hill folk yet live among the rural people of Lancashire.” Speaking of his youth in the first half of the century, Charles Hardwick stated that, fairies had then been “as plentiful as blackberries-” but this no longer seemed to be the case to him considering the Lancashire of the 1870s. Researching Devon folklore in the same year, Sir John Bowring interviewed four old peasants on Dartmoor who told him that “the piskies had all gone now, although there had been many formerly.” Even so he was told a version of the common story of pixies caught stealing grain from a barn, something that had apparently happened as recently as three years before.

According to John Brand, describing Shetland in 1883, “not above forty or fifty years ago every family had an evil spirit called a Browny which served them…” Writing about the same islands in the same year, Menzies Fergusson said that:

“credulous times are long, long gone by and we can see no more of the flitting sea trow… Civilisation has crept in upon all the fairy strongholds and disenchanted the many fair scenes in which they were wont to hold their fair courts.”

Recounting Cornish folk belief in 1893 Bottrell cited a verse to the effect that “The fairies from their haunts have gone.” In Herefordshire in 1912 a Mrs Leather of Cusop, just outside Hay on Wye, recalled fairies being seen dancing under foxgloves in Cusop Dingle: a vision that was within the memory of people still living, she recorded.

Charles Sims, The beautiful is fled, 1900

“Not utterly extinct?”- fairies in the twentieth century

Twentieth century writers echoed their predecessors. Speaking of Wales in 1923 folklorist Mary Lewes recorded a-

“practically universal belief among the Welsh country folk into the middle of the last century [which] is scarcely yet forgotten.”

She blamed education and newspapers for having quenched the people’s spirits: “mortal eyes in Cambria will no more behold the Fair Folk at their revels.” She lamented that “even the conception of fairies seems to have been lost in the present generation.” A couple of years later, reflecting on Western Argyll in the 1850s, another writer reminisced over the “dreamland” people had inhabited before “the fierce eye of bespectacled modern omniscience” had dispelled belief. “These were the days of elemental spirits, of sights and sounds relegated by present day sceptics to the realm of superstition or imagination.” By the 1920s only old people recalled the wealth of folktales. The fairy faith was also felt to be going or gone by this time from Herefordshire, Shropshire and from the Lake District.

Towards the end of last century, describing Sussex folk belief, Jacqueline Simpson declared that:

“Although it is most improbable that a belief in fairies is seriously entertained by any adult of the present generation, it was a different matter of the nineteenth century… Even one generation ago, it was not utterly extinct.”

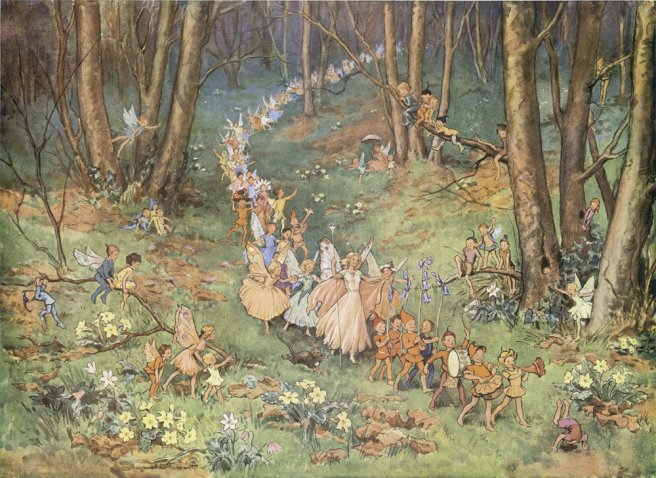

Margaret Tarrant, The fairy way

The fairies travel yet?

Continually, then, it seemed to investigators to be the case that fairy belief had been strong until a generation or so ago, but had since expired. This was asserted every few decades, and little in substance really separates the remarks of Reginald Scot from those of Jacqueline Simpson. For this reason, when Robin Gwyndaf alleged in 1997 that “fairy belief persisted in Wales until the late 1940s or early 1950s,” how confident should we be in the red line he seeks to draw? Plenty of writers have done the same before, and have found themselves subsequently contradicted. Equally, too, there have been writers- perhaps wiser, certainly more cautious- who have not been so ready to pronounce the fairies’ obituary.

As already noted, the fairies were declared dead and gone from the Lake District in both 1825 and the early twentieth century. Another observer was not so pessimistic: “The shyness of the British fairy in modern times has given rise to a widespread belief that the whole genus must be regarded as extinct,” wrote a Mrs Hodgson, yet she felt confident specimens could still be found in remote Cumberland and Westmorland neighbourhoods. In the 1870s Francis Kilvert was told by David Price of Capel-y-ffin that “We don’t see them now because we have more faith in the Lord and don’t think of them. But I believe the fairies travel yet…” In 1873 William Bottrell confidently wrote that, in West Cornwall, “belief in the fairies is far from being extinct…” On the Isle of Man it has been said that the fairies have retreated from the noise and disturbance of modern human life- but that they are still there, in the remote glens and moors.

Conclusions

Have the fairies disappeared? It seems that it all depends on who does the asking and who they’re talking to. The evidence of the recent Fairy Census, and of Marjorie Johnson’s collection of sightings in Seeing fairies, suggests that- contrary to all reports- the fairies are still present and active.

The scattered, individual accounts may give a contemporary observer the impression that the fairy faith is lost. Nonetheless, with a little perspective, with the passage of a few years, a glance back will reveal that witnesses are still meeting our Good neighbours: they may be less willing to speak publicly about these experiences than once would have been the case, but the anonymity of an on-line survey permits confessions that seem to confirm that, indeed, ‘the fairies travel yet.’

An expanded version of this text will appear in my next book, Faeries, which will be published by Llewellyn Worldwide next year.